Over 100 Americans die every day from opioid overdose, that’s about 40,000 a year. What can be done to reverse the recent spike in fatalities? In San Francisco, a team of public health workers is focused on treating the most vulnerable: homeless people on the city’s streets. My latest report for the BBC explores how this special ops “Street Team” is finding and convincing people to get the latest medical treatment, wherever they are.

It’s a timely issue as next month, San Francisco voters will decide if the city’s largest businesses, many of them tech companies, should pay a special tax to help fund more homeless shelters and addiction centers like the one I visited. The debate is dividing the tech community. Marc Benioff of Salesforce says “homelessness is everyone’s problem” and backs the special tax, but others like Twitter’s Jack Dorsey say it’s “unfair.” Love it or loathe it, the ballot measure proposes more funding and action to tackle homelessness and drug addiction in our most vulnerable population. These are complex and deep rooted problems with no quick fixes, but I applaud Marc Benioff and others like him for taking a stand.

Several medical workers and a heroin addict shared their ‘dream’ solutions to homelessness and addiction in the city. Their answers may surprise you.

If I had a magic wand, I’d just flash over the Twitter building, the Google building and say: hey guys, how about some compassion for folks, some kindness? When somebody talks to you in the street, look them in they eye. Planting that little seed of compassion and kindness goes a long way and I think that’s how the larger change in our city would happen. There’s a lot of hostility, a lot of misinformation. So if I had a magic wand, I’d just like flash it and say: compassion, compassion, compassion…kindness and a safe injection site! Ana Cuevas, health worker at the Tom Waddell Health Center, SF Public Health [Pictured above]

Listen to my report at the BBC’s Health Check Program (Ebola episode: starts at 8:49)

Check out the Fresh Dialogues podcast or below

Here’s a transcript of my full report. A shorter version aired on the BBC World Service on October 24, 2018.

Atmos: San Francisco city street sounds: bus, cars, fans, people…

Alison van Diggelen: I’m here at City Hall in the center of San Francisco. Within yards of the building’s gleaming dome, there are clusters of homeless people, huddled in doorways, sprawled on pavements, or slowly pacing the streets.

Every week, Dr Barry Zevin and his team walk the city streets to build rapport with homeless people with addiction problems and offer on-the-spot treatment. Once trust is established, they encourage patients to visit the city’s public health clinic. Today, there’s a steady stream of homeless people…

Alison van Diggelen: Inside this clinic, known as the Tom Waddell Health Center, I meet James (not his real name) a former medic in the United States army, who recently started treatment for heroin addiction.

James: Right now I got a prescription refilled, and the doctor was like: do you need a shelter bed for tonight? Are there other things I can do for you? I’m very impressed with how kind and helpful they are…going above and beyond to find what else they can do for me.

James: Right now I got a prescription refilled, and the doctor was like: do you need a shelter bed for tonight? Are there other things I can do for you? I’m very impressed with how kind and helpful they are…going above and beyond to find what else they can do for me.

Alison van Diggelen: James, who’s 30, has been prescribed buprenorphine to help wean him off his opioid addiction. Buprenorphine is a daily pill that reduces opioid cravings and the extreme physical pain of withdrawal. Despite being an addict for over ten years, James sincerely wants to change.

James: This medication allows me to do a detox less painfully and I no longer will have intense cravings for the substance of abuse. It’s definitely more comfortable than cold turkey…

Alison van Diggelen: James has been homeless in SF for about five months, after moving from Seattle. Being on the streets compounds his challenges as he faces fear and loneliness, as well as drug dealers.

James: I moved to this city not knowing a whole lot about it, so the areas I go, I’ve only operated in them under addiction scenarios. So being on something that blocks the receptors…I’m not so prone to go back to using it and therefore I can operate in these areas where there’s a lot of environmental triggers without having to…feel the same feelings of craving, to want to use.

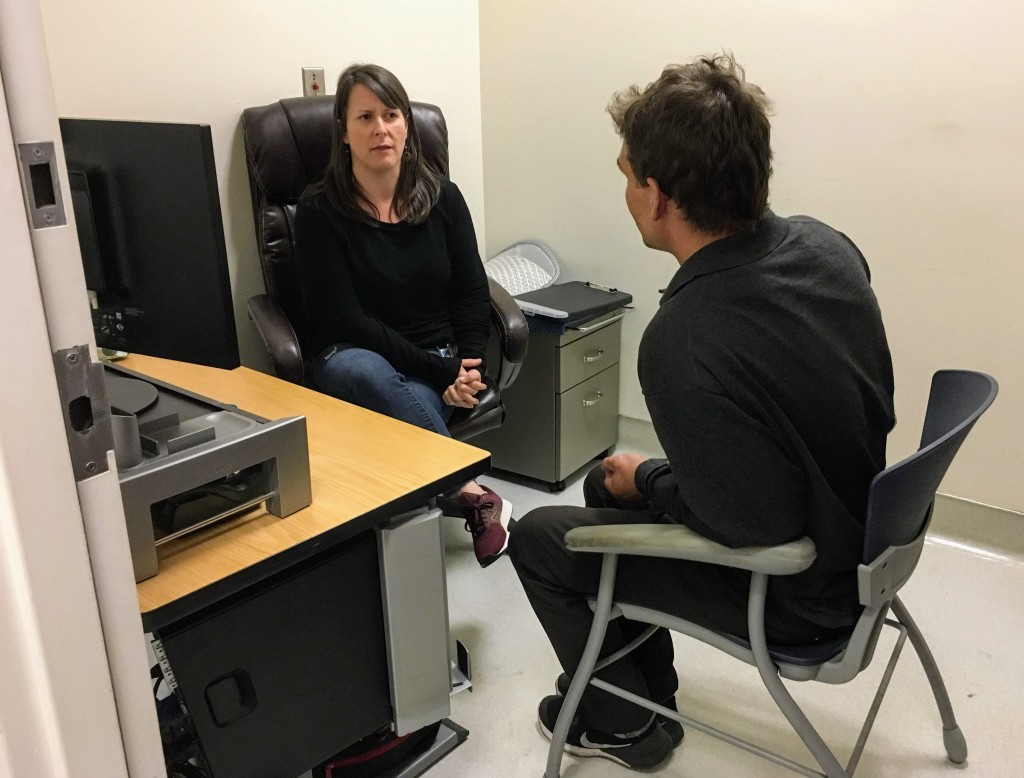

Alison van Diggelen: Sarah Strieff is a registered nurse with the SF Public Health’s “Street team”. They regularly walk the city streets to identify vulnerable patients in need of healthcare and detox. As they pound the pavements, how does she and her team convince homeless people like James to start treatment?

Nurse Sarah Strieff [pictured above]: There’s two ways we identify people: our own outreach and street presence; and through other agencies in the city that bring people to our attention.

Alison van Diggelen: Sarah, who wears ripped jeans and a T-shirt explains how being inconspicuous, non-threatening is key to their outreach.

Sarah Strieff: It’s casual, we dress down, we don’t wear uniforms.

Alison van Diggelen: No lab coats?

Sarah Strieff: No lab coats. No! We talk to people where they’re at…We’ll go to Golden Gate Park, the Haight, Bay View…I do see a lot of people hanging out in the Tenderloin.

Alison van Diggelen: The clinic serves between 10 and 20 homeless people during its daily 4-hour clinic. No appointments are necessary and you don’t need insurance. Ana Cuevas works with Sarah on the “Street Team.”

Ana Cuevas: We try to build a relationship first and check in with folks. That’s the reason why our program is so successful. Everyone who works here sees people first, then patients. Check in and ask what they need and try to deliver, not impose my own agenda on them.

Alison van Diggelen: The clinic delivers a comprehensive health care treatment plan, prescriptions for detox medications and even helps patients find a roof for the night.

Alison van Diggelen: The clinic delivers a comprehensive health care treatment plan, prescriptions for detox medications and even helps patients find a roof for the night.

Starting conversations about drug use is a sensitive process, and it takes weeks, months, even years for the Street Team to build trust with people on the street and at needle exchange facilities. For that reason, I wasn’t allowed to go on their rounds with them.

Ana Cuevas: It’s not hello: what’s your social security number, what’s your medical history? No, it’s like: who are you? How can we help you? We just listen… we just go with the flow.

Alison van Diggelen: Ana Cuevas describes the process as “Motivational interviewing” which involves a lot of listening, and no judgment.

Ana Cuevas: If someone comes in and says: Hey Ana, I’ve been using a lot. I’m not going to say: you shouldn’t do that! (instead): what are your thoughts around that? What’s happened with that? And then just kinda carry that conversation like that. One of the biggest problems with health care is that there’s often not enough time to listen. That’s the root of motivational interviewing: being present, listening and then figuring out solutions together.

Alison van Diggelen: Dr Barry Zevin is the Medical Director of Street Medicine and his team treats about 500 homeless patients a year, many of whom are addicted to opioids.

Dr Barry Zevin: When we treat them with buprenorphine or methadone – long acting, continuous stimulation of these receptors in the brain, without the sudden highs and sudden withdrawals that come with a short acting drug – these longer acting medications can really change and repair what the dysfunction of the brain is and all of the physiological stress responses people have. The physiology of someone using street opioids has really gone wrong, and that causes depression, anxiety, stress, physical disease, decreases in the immune system…a whole cascade of things go wrong that can go right when we replace that with long-acting, high affinity to the opioid receptor in the brain medication.

Alison van Diggelen: The health worker, Ana Cuevas, recalls a twenty year-old woman the team was able to help and within a week she was reunited with her family and on the road to recovery.

But Dr Zevin admits such cases are outliers.

Dr Barry Zevin: We’re in era of fentanyl contaminated drugs. It’s found its way into the drugs…They’re super potent…The risk of overdose is much higher now than it was 5 years ago. I’m talking with people every day and any day they’re at risk from having an overdose or fatal overdose bc of this new trend in drug supply.

Alison van Diggelen: The clinic treats a small percentage of the estimated 20,000 intravenous drug users in San Francisco, but Dr Zevin insists it has ripple effects. By targeting the most vulnerable people and achieving results, he’s convinced it inspires others to get treatment. He considers it a remarkable success that about one third of his patients are still in touch with the team and on treatment after a year.

Dr Barry Zevin: I always describe our model as effective but not very efficient.…We see them a lot. Once a week is not enough for some patients. With the level of instability, the level of things that can happen to people..If people are in a street or a park or a shelter, it’s a lot easier to bring the medical care to them, than wait in an office for them to finally make it to an appointment.

Alison van Diggelen: This SF program is just one of several similar schemes across the United States in Boston and in Texas. They’re often run in conjunction with needle exchanges and low barrier shelters, so that addicts can get the full support they need. Is the solution policy changes, more shelters and more funding? Healthcare worker, Ana Cuevas offers a more profound insight.

Ana Cuevas: Honestly, the most challenging part is changing the way our larger community views our population. Our folks, a lot of their humanity has been taken away…

If I had a magic wand, I’d just flash over the Twitter building, the Google building and say: hey guys, how about some compassion for folks, some kindness? When somebody talks to you in the street, look them in they eye. Planting that little seed of compassion and kindness goes a long way and I think that’s how the larger change in our city would happen. There’s a lot of hostility, a lot of misinformation.

So if I had a magic wand, I’d just like flash it and say: compassion, compassion, compassion…kindness and a safe injection site!

Alison van Diggelen: This viewpoint is echoed by James, the drug addict who recently started treatment.

James: It’s a matter of empathy I think. I would ask anybody in charge of policy…people might not seem kind or deserving of help, but they’re all people who may be in different stages of grief or suffering and to realize that it takes kindness to bring it out.

Alison van Diggelen: What are his hopes for the future?

James: I’m trained as a chef, I worked as a medic in the military. There’s things in both these fields I’d like to be doing…

END

Find out more

About the SF Ballot Proposition C plus good discussion on KQED Forum

About the Tom Waddell Clinic

About Homelessness in San Francisco

About other Inspiring Women in the Fresh Dialogues Series